Keepers, Surfmen, Wives, and Daughters: A Study of the Men, Women, and Families of the United States Life-Saving Service in North Carolina

- Tammy Woodward

- Mar 30, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: May 23, 2025

by Tammy Woodward

It was 3’oclock in the morning on August 17, 1899, when Surfman Rasmus Midgett headed south on horseback along the beach for his shift of patrolling the shoreline for signs of shipwreck.[1] Hatteras Island in North Carolina’s Outer Banks was in the midst of a hurricane, one for the history books and later named the San Ciriaco storm, so the odds of finding a wreck were high.[2] A few miles from his station, the Gull Shoals Lifesaving Station on Hatteras Island, Midgett noticed cargo and other debris scattered amongst the crashing waves. This was definitely a sign of a wreck. He continued south, despite the over wash nearly reaching his horse’s belly, until he finally heard muffled shouts over the wind. The barkentine, Priscilla, sailing out of Baltimore had run aground yards from the beach in the storm’s 100 mph winds halfway between the Gull Shoals Station and Little Kinnakeet Station to the south.[3] Midgett realized he had a decision to make.[4] Return to the station to report to the Keeper to gather gear and deploy the surfboat with his fellow surfmen to respond to the wreck, which could take hours, or take to the waves in the dark and try to save as many of the ship’s crew as possible. Midgett chose the latter.

After several hours, swimming out and back again in the crashing waves, Midgett managed to save the ship’s ten surviving crew, including the barkentine’s captain, Benjamin Springsteen, who had just witnessed the loss of his wife and son who washed overboard at the ship’s initial grounding.[5] Rasmus Midgett received the Gold Lifesaving Medal of Honor for his selfless act; he was the ninth North Carolina Surfman to receive that honor.[6] He was also a member of a remarkable government service dedicated to rescuing distressed mariners along America’s coastlines; one that was especially tough along the shores of North Carolina.

The Outer Banks of North Carolina is both a beautiful and dangerous place. Its chain of windswept barrier islands stretches from the coastline of Virginia south to Cape Lookout. Its waters contain the ghostly graves of an estimated 3,000 shipwrecks spanning four centuries as a result of horrific storms, dangerous shoals, shifting sandbars, and unforgiving winds. The United States Life-Saving Service (USLSS), which operated between 1874 and 1915 in North Carolina, is a history that is near and dear to the Outer Banks community. The region is filled with descendants of the Keepers and Surfmen who once manned the USLSS stations that the federal government built along America’s coastlines. Lifesaving stations were a government solution to the growing public outcry over the staggering number of deaths by shipwreck, often happening within yards of the beach, during the early nineteenth century. After a long legislative battle and a particularly infamous year of shipwrecks between 1870-1871, Congress appropriated funds to create the United States Life-Saving Service under the Department of the Treasury and placed the enigmatic, forward-thinking Sumner L. Kimball in charge of its administration. By the turn of the next century, 279 lifesaving stations dotted the Atlantic, Pacific, and Great Lakes coasts.[7] The USLSS was a government success story that saved thousands of lives until its eventual merge with the United States Revenue Cutter Service to form the U.S. Coast Guard in 1915. It also left an indelible legacy among the coastal towns and communities of America’s coastline.

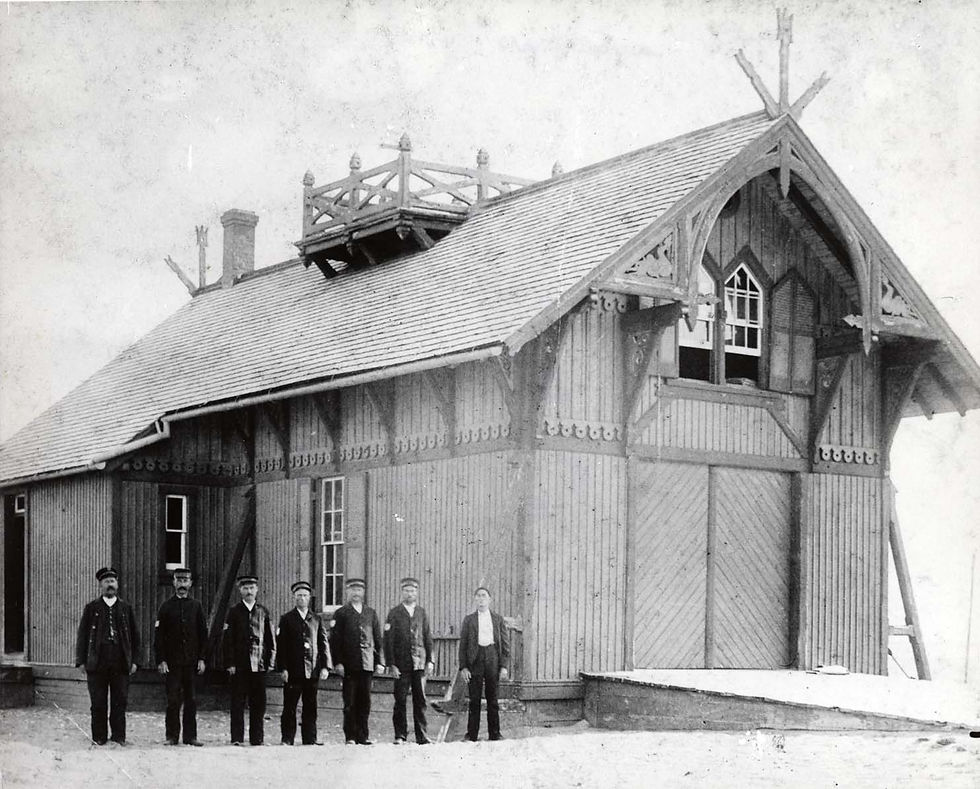

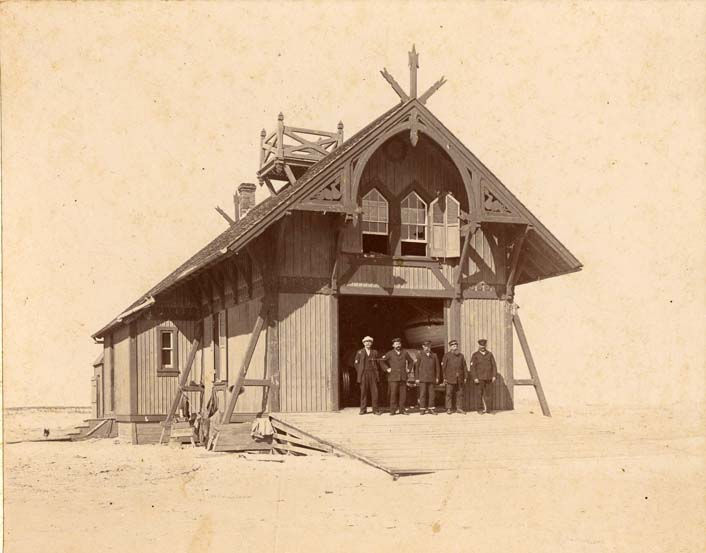

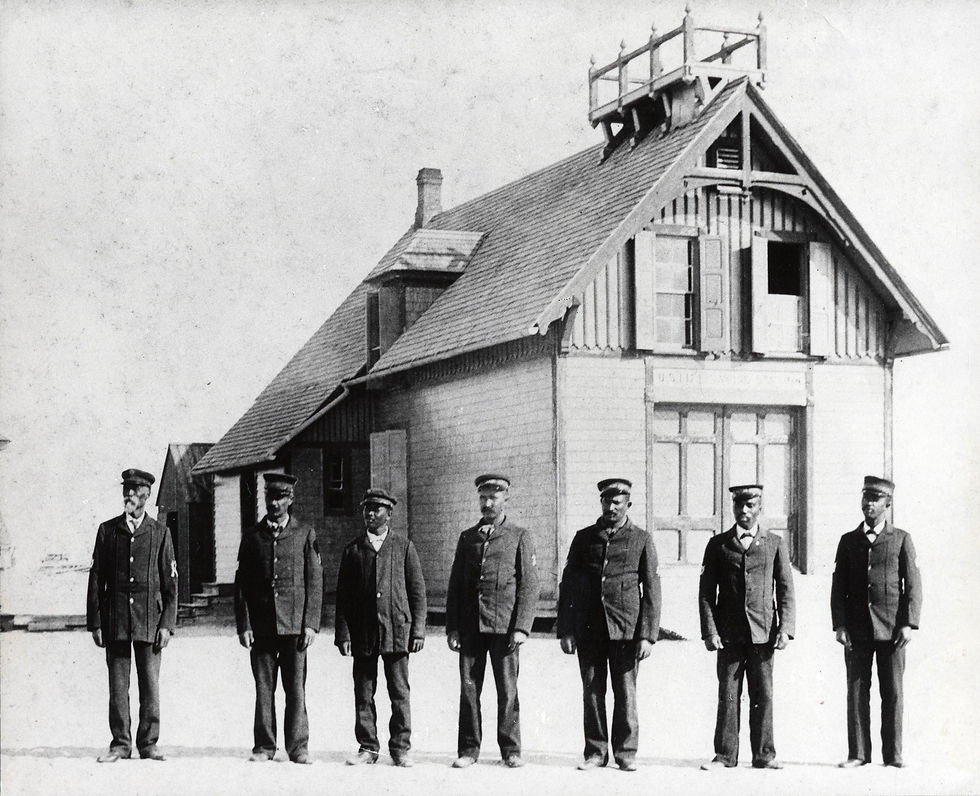

The coast of North Carolina once hosted a chain of twenty-nine lifesaving stations crewed by the bravest of men who fostered close-knit coastal communities of hardy families. Each station employed a Keeper and six Surfmen ranked one through six according to experience. These men formed a new breed of masculinity that was founded on bravery, selflessness, and physical endurance that sparked a national following in the popular press of their brave deeds and heroic rescues. These men embodied the myth of lifesaving: “they had to go out, they did not have to come back,” and served as lifesavers with bravery, selflessness, and physical endurance that sparked a national following in popular newspapers of their brave deeds and heroic rescues.[8] Surfmen were portrayed as romantic, heroic figures in literature and the popular press. The surfman of the lifesaving service emerged as the model male in newspapers and the occupation of lifesaving embodied ideal manhood for American readers. Headlines read, "Real Men in the Life-Saving Service," who created "the best of the schools in which men are made."[9] They embodied the myth of lifesaving: “they had to go out, they did not have to come back” that is still used by the Coast Guard today.[3] What is lesser known is the distinguished role their wives, sisters, sweethearts, and daughters played in the benevolent mission of lifesaving or the kinship networks that formed around station life in these isolated, coastal communities.

While the Life-Saving Service has fostered a small but detailed historiography, its focus has largely been on adventure stories of dramatic shipwrecks and rescues; the military-style training, drills, surfboats, and beach apparatus employed by the crews; the unique architecture of station buildings; and the legislative battles fought in Congress to grow and expand the service. This dissertation will not recount the history of the USLSS, at least no more than is necessary to understand its distinct origins. Rather, this dissertation will introduce readers to the social fabric of the lifesaving service and to the caliber of men and women who undertook its livelihood.

The purpose of this dissertation is to reexamine the United States Life-Saving Service using a combined social, gender, and kinship perspective to focus on the experiences of the men who chose this honored way of life, and the women and families who served alongside them, who together left an indelible stamp in the coastal communities along America’s shores. Using a case study of North Carolina’s Outer Banks, this dissertation will situate the men and women of the lifesaving service within the broader nineteenth-century contexts of gender and the family. It will focus on traits like bravery, hardship, and sacrifice that compelled these lifesavers to routinely rescue distressed mariners in turbulent offshore seas as an occupation and a calling.

Chapter Two will set the stage for this study by briefly chronicling the development of the United States Life-Saving Service and its expansion into North Carolina. By re-examining the specialized training, drills, and equipment together with the natural skills of the lifesavers – only from the men’s perspective – this research will illustrate the rigorous day-to-day readiness that kept surfmen conditioned to respond to shipwrecks and endangered mariners at a moment’s notice. This chapter will also discuss the volatile weather and unforgiving landscape of the Outer Banks as a backdrop to the lifesaving service. It will introduce readers to the beautiful yet dangerous shores of the North Carolina coast and address the question of how nature played a dominant role in lifesaving and acted as a measure of the men in its service.

The next Chapter will explore how the men who joined the lifesaving service created a unique code of coastal manhood that transformed into something different from traditional nineteenth-century ideologies of manliness. It will show how the social constructs of masculinity among Keepers and Surfmen took on a regional identity and how their efforts fostered the development of isolated coastal communities like the Outer Banks. The latter nineteenth century experienced a major turning point in national definitions of manhood as a result of the Civil War. Ideals of masculinity underwent significant shifts within the greater changes of social, political, cultural, and technological modernity. This chapter will answer the question of how lifesavers represented a new breed of coastal masculinity that stood out from the sedentary domestic man, the civilized urban man, or the southern gentleman of the latter nineteenth century. For instance, it will define the sense of brotherhood and community among the lifesavers, such as in 1903, when the men of Kill Devil Hills Lifesaving Station fed, housed, and fostered two brothers from Ohio, Orville and Wilbur Wright, throughout their trials for first flight.[11]

The idea of coastal masculinity will be taken a step further in Chapter Four with an investigation of how the early integration of the USLSS allowed surfmen of both the Black and White races to cross traditional racial barriers to serve together as one service. It will explain how African American surfmen also shaped coastal manhood into a selfless service as they used their expert skills as watermen to save distressed mariners regardless of ethnicity or nationality. Scholars of southern manhood often define characteristics of masculinity along occupational, class, and racial divides. This chapter will explore how masculinity, along with social characteristics like class and race among lifesavers, took on a regionalized identity as traditional southern manhood blurred in the occupation of shipwreck rescues along the remote beaches of North Carolina. Did these progressive social ideals develop simply out of a shortage of available men among isolated beach communities, or were they unique to the individuals who settled on the coast and braved the weather and sea to serve under the USLSS?

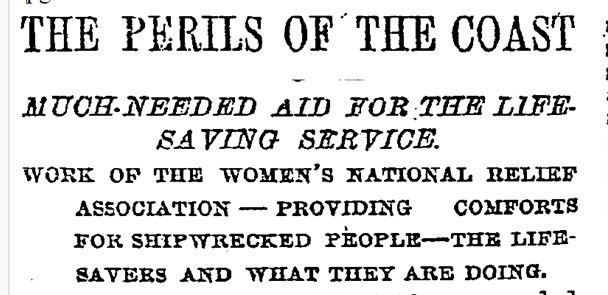

Shifting gears, Chapter Five will examine the crucial support roles of women outside of the service to show how their volunteership enhanced the service and contributed to its longevity. While the U.S. Lighthouse Service employed women as Lighthouse Keepers in the nineteenth century, the U.S. Life-Saving Service never formally hired women as Keepers or Surfmen; they served strictly in a volunteer capacity. The records of the USLSS describe women backfilling surfmen’s roles at the stations and at home while the men spent hours and even days on the water responding to a wreck, and yet little has been written about them. Women served as cooks, nurses, and helpmates to lifesaving station crews and the individuals they rescued. They billeted the wives and children of rescued ships’ crews in their homes and maintained small gardens and livestock to supplement the coastal diet. This research will fill that gap to show how wives and daughters augmented the men’s roles out of necessity and crossed traditional gender barriers to fulfill a shared mission of saving distressed mariners imperiled by the sea.

The wives of lifesavers also joined the volunteer organization known as the Women’s National Relief Association that employed newspaper advertisements and wealthy city elites, like President James A. Garfield’s first lady, to solicit donations of clothing, food, and necessities to send to stations for shipwreck victims.[12] The nineteenth century experienced a major turning point in women’s organizing for charitable causes; and so, in Chapter Five, this study will situate how women used this national platform to benefit the lifesaving stations within that broader context. These efforts were supported and documented in shipwreck reports and in the annual reports of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, so they were clearly sanctioned by its headquarters. Much like their men, these women formed a new breed of coastal womanhood that set them apart from their counterparts further inland. Were these women simply helpmates to the lifesavers, or were they instrumental partners that served as supply organizers, cooks, nurses, farmers, fishermen, and substitute lifesavers when circumstances demanded it?

In addition to men’s service and women’s volunteership in the lifesaving service, in Chapter Six, this study will address a lesser-known component of lifesavers, that of the kinship networks that formed among lifesaving station communities. In nearly all stations across the country, Keepers and Surfmen served in a multi-generational capacity with common surnames emerging among the crew lists and sons serving under fathers and uncles or intermarrying with nearby station families. This was especially true in North Carolina. Although the historiography alludes to the lifesaving service as a family business, this research will seek to discover whether this phenomenon was simply based on a lack of prospects or if it was a higher calling that was passed down from generation to generation. Primary evidence suggests the latter based on the number of descendants of the USLSS crewmen who served in the Coast Guard.

Overall, this research will investigate how nineteenth-century ideologies of masculinity and femininity were transformed under the lifesaving service’s culture and policies to foster nationally-recognized heroism, sacrifice, and survival within the isolated beach communities of the North Carolina coast. The result was a dramatic decrease in lives lost to shipwrecks along America’s shores, and a culture of heroism that carried forward into the U.S. Coast Guard. This study will marry the history of the Life-Saving Service through its government records with new research using a variety of uncharted archives of the Outer Banks like oral histories, local family papers, and local station records to define coastal ideologies of manliness, nontraditional womanhood, and kinship roles in the lifesaving service. The results will bring to life the unique individuals who served as lifesavers and honor their lived experiences that sparked a national following and a century of adventure stories. By analyzing lifesavers through a social, family, and gender lens, this research will add a new dimension to the small but detailed historiography of the United States Life-Saving Service.

Tammy Woodward is a resident of the Outer Banks in North Carolina and a doctoral candidate in the Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in American History program at Liberty University. She is the Director of the Outer Banks History Center, the eastern branch of the State Archives of North Carolina. She also serves on the board of directors for the Outer Banks Coast Guard History Preservation Group, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization that aims to preserve the surviving lifesaving stations of the Outer Banks.

Bibliography

"A New Humane Society: Work in which Mrs. Garfield is Interested. The Victims of Shipwreck, Famine, and War to be Aided, What the Women's National Relief Association Proposes to Do." New York Times (June 15, 1881): 2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Carol Cronk Cole Collection. AV.5138. Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina, Manteo, North Carolina.

Charles Evans Collection. AV.5205.3. Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina, Manteo, North Carolina.

David Stick Papers. PC.5001. Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina, Manteo, North Carolina.

H. H. Brimley Collection. AV.5197. Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina, Manteo, North Carolina.

Kelly, Fred C. The Wright Brothers: A Biography Authorized by Orville Wright. San Francisco, CA: Golden Springs Publishing, 2017.

Mobley, Joe A. Ship Ashore!: The U.S. Lifesavers of Coastal North Carolina. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Office of Archives and History, 1994.

National Parks Service Photographs. AV.5178. Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina, Manteo, North Carolina.

Noble, Dennis L. That Others Might Live: The U.S. Life-Saving Service, 1878-1915. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994.

“The Perils of the Coast,” New York Times, January 8, 1882. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Rennie Fuqua United States Lifesaving Service Photographs Collection.AV.5188. Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina.

Shanks, Ralph, and Wick York, The U.S. Life-Saving Service: Heroes, Rescues, and Architecture of the Early Coast Guard. Novato, CA: Costano Books, 2004.

United States Lifesaving Service. Annual Report of the United States Lifesaving Service, 1899. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1900.

Yates, Snowden. “Winning the Badge of Courage, Real Men of the Life-Saving Service Who Got the Coveted Treasury Medal.” The Morning Telegraph, 1911. Clipping. John F. Wilson IV Papers. PC.5359. Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina, Manteo, NC.

[1] United States Lifesaving Service, Annual Report of the United States Lifesaving Service, 1899 (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1900), 26-27.

[2] Dennis L. Noble, That Others Might Live: The U.S. Life-Saving Service, 1878-1915 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994), 134.

[3] United States Lifesaving Service, Annual Report 1899, 25.

[4] Joe A. Mobley, Ship Ashore!: The U.S. Lifesavers of Coastal North Carolina (Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Office of Archives and History, 1994), 125.

[5] Noble, That Others Might Live, 136.

[6] Mobley, Ship Ashore!, 127.

[7] Ralph Shanks and Wick York, The U.S. Life-Saving Service: Heroes, Rescues, and Architecture of the Early Coast Guard (Novato, CA: Costano Books, 2004), 17.

[8] Mobley, Ship Ashore!, 7.

[9] Snowden Yates, “Winning the Badge of Courage, Real Men of the Life-Saving Service Who Got the Coveted Treasury Medal,” The Morning Telegraph, 1911, Clipping, John F. Wilson IV Papers, Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina, Manteo, NC.

[10] Joe A. Mobley, Ship Ashore!: The U.S. Lifesavers of Coastal North Carolina (Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Office of Archives and History, 1994), 7.

[11] Fred C. Kelly, The Wright Brothers: A Biography Authorized by Orville Wright (San Francisco: Golden Springs Publishing, 2017), 65.

[12] "A New Humane Society: Work in which Mrs. Garfield is Interested. The Victims of Shipwreck, Famine, and War to be Aided, What the Women's National Relief Association Proposes to Do," New York Times (June 15, 1881): 2.

Comments